Haciendas and Ejidos

Mexico had a highly agricultural economy from pre-colonial times through the mid-20th century. In the 19th century, haciendas—large plantations—were both the dominant form of land ownership and favored by the Diaz government.

Farming on a small scale has not been developed in Mexico on account of unfavorable conditions for the small land holders. The large estates, called haciendas, pay only about 10 percent of the taxes levied by law...while the small landholder is obliged to pay the whole tax imposed...as he lacks the political influence to obtain a reduction.

Above: Luis Cabrera, The Mexican Situation from a Mexican Point of View

Due to the aggressive buying tactics of foreign companies and hacienda owners, 68 million acres of land had been possessed by land companies. By the end of the Porfiriato, roughly 95% of villages lost their ejidos and the purchasing power of peons decreased to less than half of what it was at the start of the 19th century.

The communal lands formerly owned by the towns, and which were called ejidos, were, since about 1860, divided and apportioned among the inhabitants for the purpose of creating small agricultural properties, but...those lands were almost immediately resold to the large land owners which properties were adjacent. This resulted in strenthening the oppressive monopoly excercised by the large land owners, as the small properties were unable to withstand the competition.

Above: Luis Cabrera, The Mexican Situation from a Mexican Point of View.

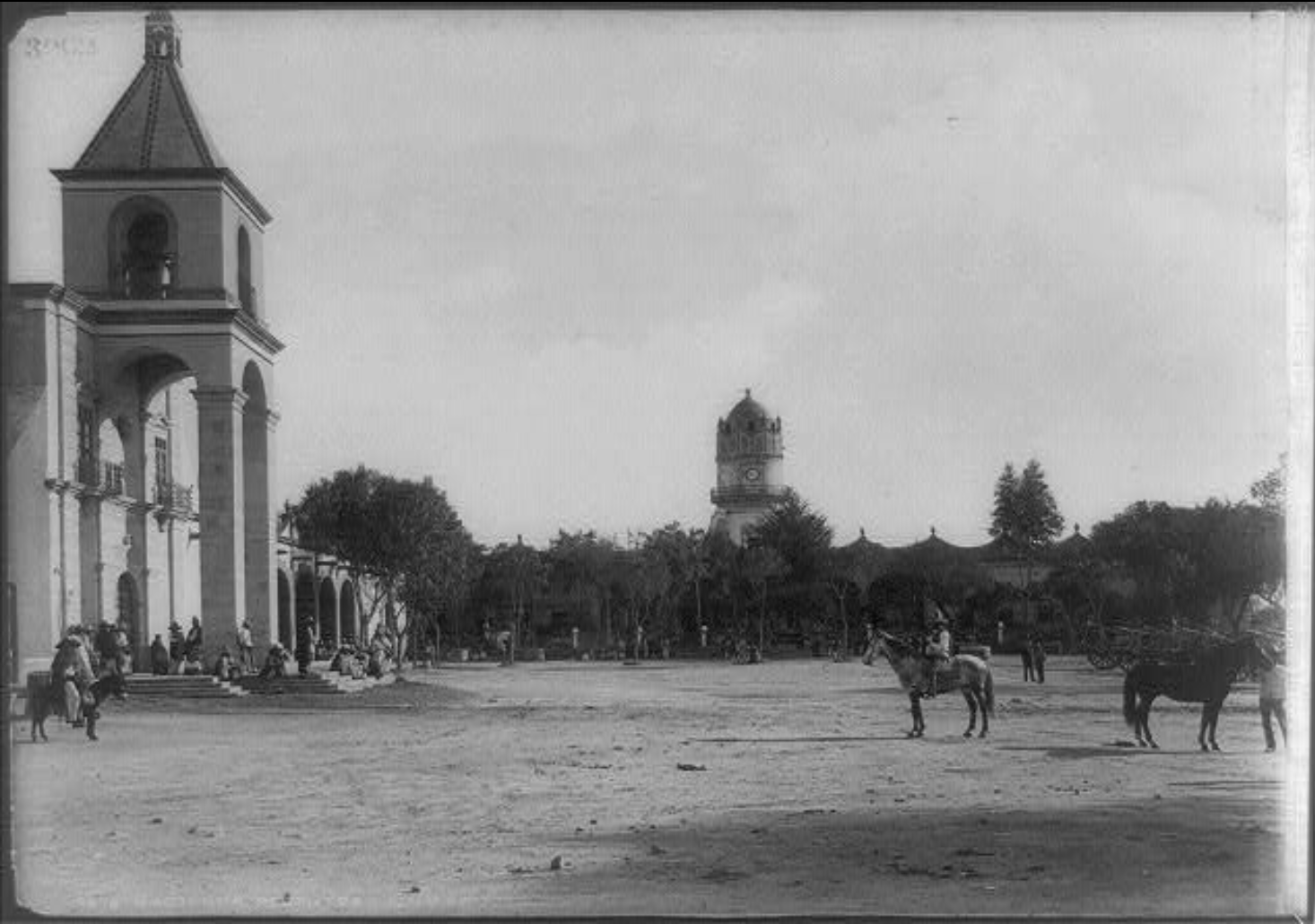

Above: Hacienda Peotillos: [Courtyard]. 1884.

The ejidos and their own have been the origin of very important economic phenomena developed in our country. Anyone who has read a land title from the colonial era can feel how the struggle between the haciendas and the towns transcends every page of the title of a hacienda or a town.

Above: Luis Cabrera, "La Reconstitución de los Ejidos de los Pueblos."

As a counterpoint to haciendas, many villages contained ejidos, publicly-held land available to all in the village. Peasants supplemented their meager earnings by growing and taking resources from ejidos.

The ejidos assured the people of their subsistence...the ejidos ensured tranquillity of the families gathered around the village church...The villagers were, in effect, communal landowners rather than individual owners of large landed estates. This was the secret behind the preservation of the villages in the face of the hacienda, in spite of the great political privileges held by Spanish landowners during the colonial period....I would not say that all of the [ejidal] land was usurped, although much of it was; I will not say that all of the land was stolen with the connivance of the authorities, although there are thousands of such cases.

Above: Luis Cabrera, "The Restoration of the Ejido."

Diaz’s policies exacerbated the economic inequality of Mexican society. A land law passed in 1883 encouraged foreigners and wealthy hacendados to buy up public land. Land that was not proven to have a legal title attached to it was automatically considered public property. In 1894, a land law considered all "underutilized" land to be public, which made those lands applicable to the 1884 law.

Article 1. In order to obtain the land necessary for the establishment of settlers, the Executive will order the demarcation, measurement, division and valuation of the vacant land or national property that exists in the Republic, appointing for this purpose the commissions of engineers that it considers necessary, and determining the system of operations to be followed.

Article 2. The fractions will not exceed in any case two thousand five hundred hectares, this being the largest area that may be awarded to a single individual of legal age and with the legal capacity to contract.

Article 3. The demarcated, measured, divided and valued lands will be transferred to foreign immigrants and inhabitants of the Republic who wish to establish themselves there as settlers...

Above: Ley sobre terrenos baldíos, mandando deslindar, medir, fraccionar y valuar los terrenos baldíos o de propiedad nacional, para obtener los necesarios para el establecimiento de colonos. [Law on vacant land, ordering the demarcation, measurement, division and valuation of vacant land or national property, in order to obtain the land necessary for the establishment of colonists. national property, in order to obtain those necessary for the establishment of settlers.] 1883.

Article 2. All lands of the Republic that have not been destined for public use by the authority empowered to do so by the Law, nor assigned by the same for valuable or lucrative title, to an individual or corporation authorized to acquire them, are uncultivated lands.

Article 5. Waste lands discovered, demarcated and measured by official commissions or by companies authorized to do so, and which have not been legally alienated, are national.

Above: Ley sobre ocupación y enajenación de terrenos baldíos. [Law on occupation and alienation of vacant land.] 1894.

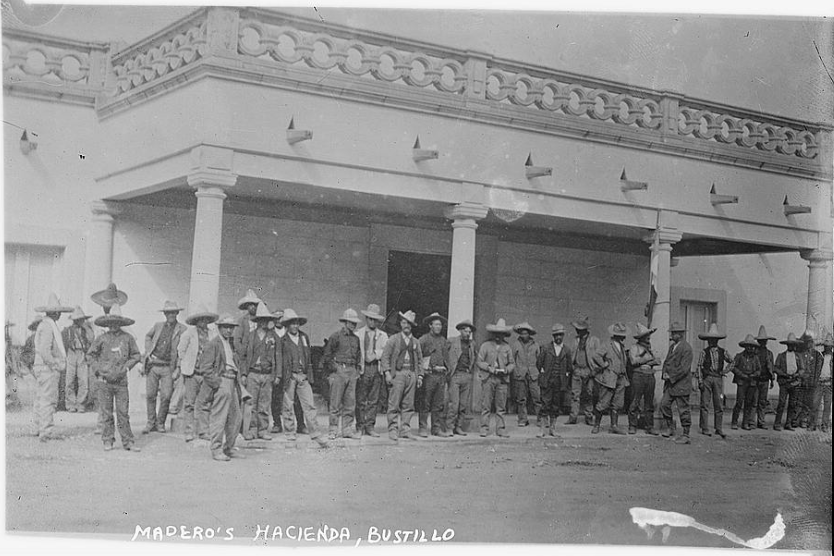

Above: Madero's Hacienda, Bustillo. 1911.