Land Distribution Post-Constitution

The immediate impact of Article 27 was rather limited. The seven presidents in power after the passing of the Constitution—Carranza, Huerta, Obregon, Calles, Gil, Rubio, and Rodríguez—started agrarian reforms in Mexico. However, poor administration of the land reform policies meant the amount of land redistributed was paltry.

Only a few lizards come out to stick their heads out of their holes, and once they’ve felt the sun’s burning, they run to hide in the shadow of a little rock. But we, when we have to work here, what will we do to cool off from the sun, eh? Because we were given these crusts of land to plant on.

They told us:

“From the village up to here, it’s yours.”

Above: Juan Rulfo, "They Have Given Us the Land"

An agricultural center of such importance attracted many people who made every effort to remain there. The landowners, in the face of that avalanche of people, gave out lands—not their good lands, of course, but marginal ones— where people settled, living very precariously. This aggravated the [agrarian and social] problem. Later [the hacendados] tried unsuccessfully to expel 15,000 farmworker families, leaving only 20,000 resident peons who were paid starvation wages.

Above: Fernando Benitez, "The Agrarian Reform in La Laguna"

Promised lands were insufficient to meet demand and of poor quality, and discontent brewed among the populace. Carranza’s government redistributed only 450,000 acres of land: some haciendas were larger than this.

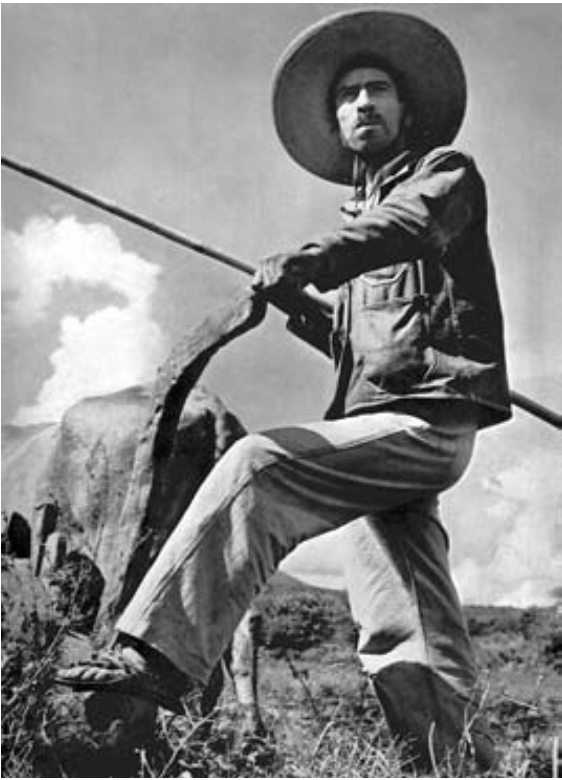

Above: Plowing in a Field of Maguey. 1931.

Above: Ejidatario (a farmer on an ejido). 1950.

There was also a lack of consistency, of arduous and sustained effort, the only kind which could lead to tangible and enduring results. It is sufficient to examine the consistency . . . of the ordinary . . . procedure by which the ejidos have been parceled out. It will be seen then that there was no consistency and that furthermore the grants of land have not always been dictated by prudence or necessity, but rather by the desire of each particular person in power to appear as the bravest dispenser of lands. Consistency in the form or logic and thoroughness also was lacking...

Above: Daniel Cosío Villegas, "Mexico’s Crisis"

Despite Cardenas' reforms, the lives of the newly-made ejidatarios—members of an ejido—did not change significantly: real wages were still depressed and living conditions were still poor.

[an ejidatario:] "Sure, but we don’t get the benefits; we just get a peso and a half per day."

[a journalist:] "But I thought that was just an advance. Don’t they distribute the profits when they sell the harvest?"

"Maybe so, but in practice there’s never anything to distribute."

"Why is that?"

"Because we still have to settle all of the debts we’ve had pending since the first year, when we barely harvested anything. And we also have to pay the Ejidal Bank so it can pay the big landowners."

Above: Fernando Benitez, "The Agrarian Reform in La Laguna"

"Comrades, we’ve called this small meeting to make you see the sad conditions we live in, and which we find it just to bring to an end. All those present here have received a plot of land so that, by sowing it and harvesting its crops, we can live in ease. But unfortunately, none of us feels happy with his land, because we don’t have the necessary resources to work it and make it as productive as it should be. It’s truly a shame to see our fields so fertile, yet not rendering sufficient fruits to support ourselves and our families. And what little they do render is snatched away from us at ridiculous, starvation prices..."

Rubén Jaramillo, "Struggles of a Campesino Leader."

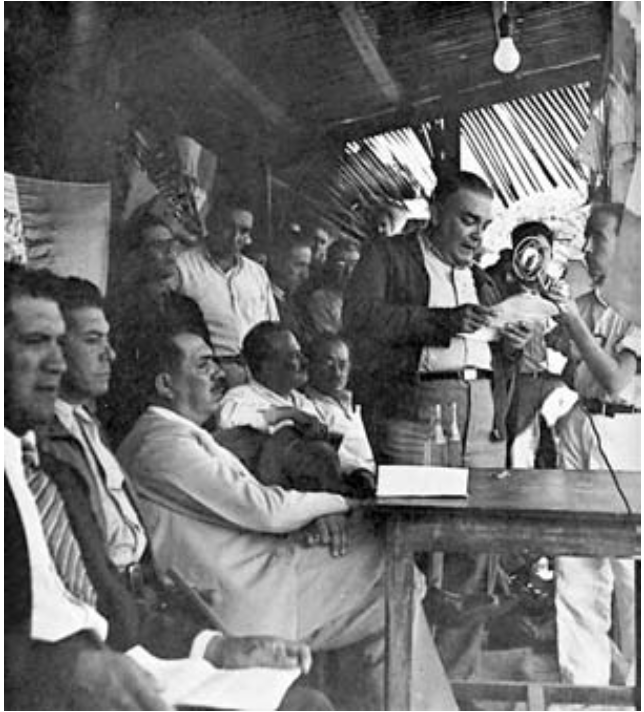

Above: Lázaro Cárdenas Presiding over a Land-Expropriation Ceremony in Michoacán. 1942.

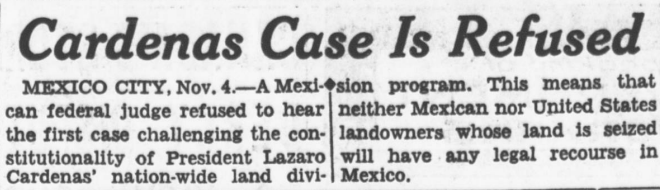

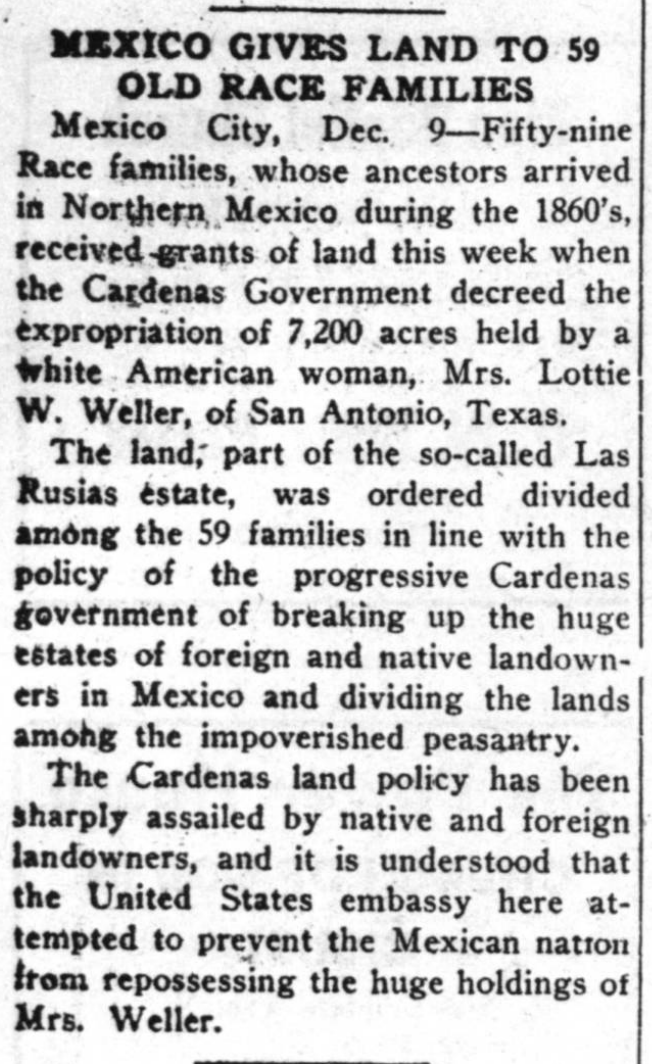

The rise of Lazaro Cardenas to the presidency was accompanied by the promise and execution of significant agrarian reforms. His promise was derived from the promise of radical land reform embedded in Article 27.

Consequently, the agrarian ideal contained in Article 27 of the General Constitution of the Republic will continue to be the axis of Mexican social issues, as long as the land and water needs of all the country's peasants have not been fully satisfied.

In this respect, the only limit for the endowments and restitutions of land and water will be the complete satisfaction of the agricultural needs of the rural population centers of the Mexican Republic.

PRI, "Plan Sexenal." The PRI was Mexico's ruling party during the revolution.

Above: "Cardenas Case Is Refused."

Above: "Mexico Gives Land to 59 Old Race Families."

Cardenas’s government redistributed more land than his predecessors combined.